Governments ease alcohol access as evidence of its harms mount

From cancer to heart disease to brain damage, the evidence of alcohol’s harms is mounting. So why are governments making it easier to drink?

By Alexandra Keeler | 5-minute read

In May, shortly after Parliament resumed, Quebec Senator Patrick Brazeau introduced Bill S-202, a private member’s bill to require nearly all alcoholic beverages to carry health warning labels.

“As a former alcohol consumer, I was once in the 75 per cent of Canadians who are not aware that there is a causal link between alcohol consumption and seven cancers,” Brazeau told the House of Commons on June 3.

“I personally battled colon cancer several years ago, so much so that when I received treatment, I felt I was being killed inside.”

Brazeau is something of an outlier in government. Public health experts say Canadian governments are not doing enough to address alcohol’s known health risks — and that the alcohol industry is a big part of the problem.

“We’ve known about the carcinogenic effects of alcohol since the 80s,” said Peter Butt, a University of Saskatchewan researcher and co-chair of Canada’s latest drinking guidelines. “But there are no warning labels, so the consumer is given false confidence.

“Some of this falls at the doorstep of the government, because they regulate the labeling.”

Alcohol harms

Today, the World Health Organization warns that alcohol harms nearly every system in the body.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies alcohol as a cause of six cancers.

Chronic alcohol use raises the risks of liver and heart disease, brain damage, mental health issues, injuries and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

In Canada, the federal government oversees labeling and public health messaging rules, while the provinces control liquor sales and drinking ages.

In January 2023, Health Canada released updated national alcohol guidelines in response to the growing evidence of alcohol-related harms. This new guidance marked a major departure from its 2011 recommendations, which had suggested women not exceed 10 drinks per week and men not exceed 15.

The new guidelines have a sober message: no amount of alcohol is risk-free, and risk rises significantly with more than two drinks a week.

“We didn’t say you shouldn’t drink more than two standard drinks a week. We said you should reduce the amount that you drink,” said Butt, who co-chaired the team that updated the guidelines.

“The consumer had a right to know.”

Mixed messages

Aside from tightening its guidelines, Canadian governments have done little to better protect the public.

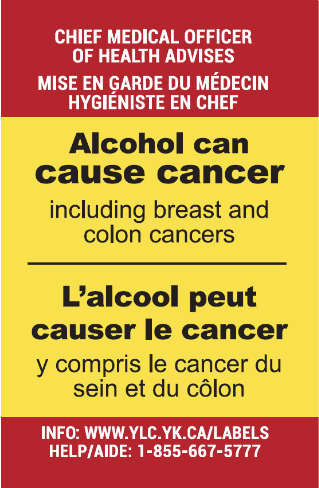

Public health experts say one major flashpoint has been warning labels. In general, drinks with greater than 0.5 per cent alcohol content are exempt from standard food and beverage labeling requirements.

“Even bottled water or non-alcoholic beer has to have the nutrition facts because it doesn’t have enough alcohol in it to get the exemption,” said Adam Sherk, a research scientist at the Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addiction who also advised on Canada’s updated alcohol guidelines.

The Canadian Cancer Society has been advocating for labels on alcohol products since 2017. The Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research has done the same since 2023. But Health Canada has not initiated any regulatory process to mandate warning labels for alcohol products.

Some research indicates such labels could reduce sales.

A 2020 study by the Yukon government and the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research tested how warning labels affect consumer behaviour. It found labels did increase awareness and reduce sales.

Yukon pulled its label requirements after the alcohol industry threatened to sue the government.

Convenient

Labelling is just one of many measures governments could take to reduce alcohol-related harm.

In addition to labels, the Canadian Alcohol Policy Evaluation project recommends minimum unit pricing, marketing and advertising controls, and public education campaigns. No province or territory has fully implemented all of these measures.

“[T]he Canadian federal government has not adopted or only partially adopted many evidence based alcohol policies,” the project’s report reads.

Meanwhile, some provinces are moving in the opposite direction.

Nova Scotia is considering expanding retail options. In April, Quebec rejected a recommendation to lower its blood alcohol limit for drivers, despite repeated coroner warnings.

Ontario has gone the furthest.

The province plans to invest $175 million over five years to grow its alcohol sector. It has begun permitting alcohol sales in convenience stores for the first time — with up to 8,500 new retailers expected to carry alcohol by 2026. It has also scrapped previous limits on pack sizes and discount pricing.

In April 2024, the province’s chief medical officer, Dr. Kieran Moore, recommended raising the legal drinking age from 19 to 21. Premier Doug Ford rejected the idea, arguing that if 18-year-olds can enlist in the military, they should be allowed to drink.

“We believe in treating people like adults,” he told media at the time.

In late June, the province also approved alcohol consumption on so-called “pedal pubs” — large, multi-person bicycles equipped with a U-shaped bar, often used for tours or bachelor parties.

“There’s never been such a large increase in availability all at once,” said Sherk, calling Ontario’s expansion “unprecedented.”

False profits

Tim Stockwell, a University of Victoria professor and former director of the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, says corporate influence helps explain why governments are failing to address alcohol’s health risks.

“Evidence for harms from alcohol has been with us for decades and has only strengthened,” said Stockwell. “Commercial vested interests have always dominated the policy sphere.”

Federal lobbying records show Beer Canada has routinely targeted Health Canada and more than two dozen federal agencies to influence policy on labeling, taxation and public health messaging. This includes closed-door meetings with MPs and senior officials from the Department of Finance and Agriculture Canada.

Beer Canada did not respond to multiple requests for comment by press time. Spirits Canada and Molson Coors Beverage Company also did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Butt, of the University of Saskatchewan, says the money governments generate from alcohol sales creates a conflict with their public health mandate.

Federal and provincial governments generate revenue from alcohol through a range of mechanisms, including excise taxes, provincial markups, sales taxes and licensing fees. In some provinces, governments also earn profits from government-run liquor stores.

“[Governments] look at it from a lost revenue perspective, rather than from a public health perspective,” said Butt.

Ian Culbert, of Public Health Canada, puts it more bluntly. “Governments have a substance sales issue, as opposed to a substance use issue,” he said. “But it’s short-term gain for long-term pain.”

“Public Health wants to reduce consumption, because all consumption contributes to harm,” said Stockwell, of the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research. “Commerce wants to … expand the consumption.”

A familiar playbook

Every expert interviewed for this story said the alcohol industry is following the tobacco industry’s playbook.

“They’re using the same sort of rear-guard action policies: denial, heavy government lobbying, government revenue,” said Butt.

“I don’t trust either the industry nor the government to do the right thing based upon past action. I think it’s important that consumers are educated.”

Adam Sherk agrees. “If I was [the industry], I would also be scared about consumers knowing this link [to cancer] better,” he said.

“The strategy is to obfuscate the link — point to studies that might be older or found no link, or put a lot of things in the water so it seems less clear than it is.”

But alcohol, experts say, is harder to regulate than tobacco. “Nobody liked to be in an airplane with smokers eating dinner next to smokers, so it was really easy to demonize smoking,” said Culbert.

“Alcohol is so ingrained in everything: we drink when we’re happy, we drink when we’re sad, we drink when we’re bored — we drink.”

Still, the normalization does not make the risks any less real. “There’s a mortality rate attached to this,” said Butt.

“And that’s the thing that is tragic — this is a modifiable risk factor.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

This essay doesn’t mention that alcohol has a lot of competition from legal and illegal marijuana; prescription drugs, all kinds of illegal drugs, Opioids Replacement Therapies, and magic mushrooms.

All of the above gets the user far higher and kills much quicker than alcohol.

Heartbreakingly reckless. Been reading for a few years about our misinterpretation of Prohibition's impact on society and health. Newer analysis suggests it wasn't the failure we were all told it was.