Critics question conclusions of new Ontario "safer supply" study

A new study links safer supply to health improvements, but critics say results are muddied by methadone use and extra supports

By Alexandra Keeler | 4-minute read

A new study that compares safer supply with a traditional approach to addiction treatment has ignited debate among addiction experts.

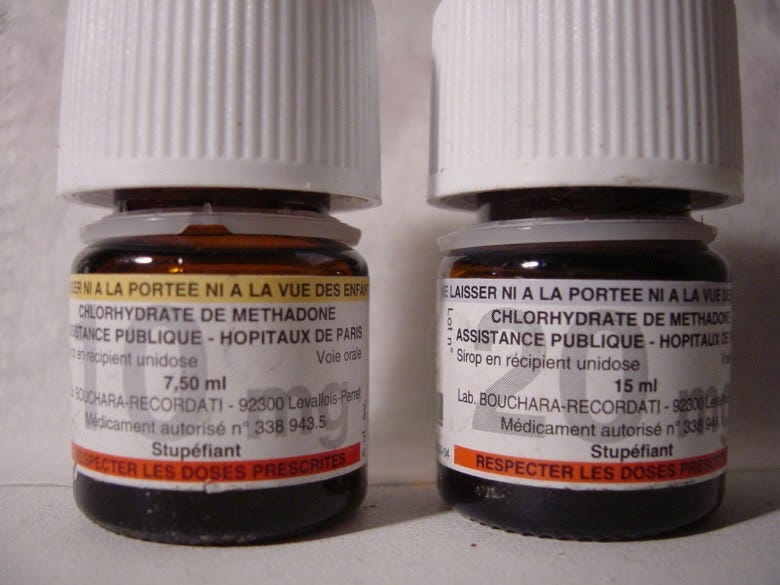

The study, published in The Lancet Public Health in April, examined health outcomes for people receiving safer supply and compared them to a similar group of people receiving methadone, a drug used to reduce drug cravings and withdrawal symptoms.

It concluded that safer supply programs significantly improved participants’ health outcomes. Safer supply provides people at high risk of overdose with prescription opioids as a safer alternative to toxic street drugs.

But critics question the study’s conclusions. They note that many safer supply participants had access to more support services and that the majority also received methadone. These factors make it difficult to identify which treatment drove the positive results.

“The study did not compare [safer supply] to methadone, but rather the initiation of both with several other unaccounted variables,” wrote psychiatrists Dr. Robert Tanguaya and Dr. Nickie Mathew in a formal critique also published in The Lancet.

Findings

The peer-reviewed study is the first in Canada to compare the health outcomes for people receiving safer supply with those receiving methadone through a program known as opioid agonist therapy. Opioid agonist therapy, or OAT, is widely used to treat opioid use disorder.

The study, which was led by teams at Unity Health Toronto, ICES, the University of Toronto and the Ontario Network of People Who Use Drugs, followed about 1,700 Ontarians who started treatment between 2016 and 2021. Half were receiving prescribed hydromorphone through Ontario’s safer supply programs; the other half were receiving methadone through an OAT program.

Participants were tracked for up to one year. Both groups saw improvements, including fewer overdoses, emergency room visits, hospital stays and new infections.

“The findings suggest [safer supply] programmes play an important, complementary role to traditional opioid agonist treatment in expanding the options available to support people who use drugs,” the study says.

However, when compared against each other, the safer supply group had higher rates of overdose, ER visits and hospital admissions than those on methadone.

Still, the authors conclude that safer supply can complement methadone, especially for people who do not respond well to traditional options like OAT.

Confounders

In their May 27 critique in The Lancet Public Health, psychiatrists Tanguay and Mathew say the study fails to isolate the effects of safer supply.

“It is unclear from this study whether the benefits attributed to [safer supply] initiation came from the prescribed … hydromorphone or not,” they wrote.

One concern is that most safer supply participants were also on methadone — a highly dose-dependent medication — and the study did not account for how much of each drug they received.

Dr. Leonara Regenstreif, a primary care physician who specializes in substance use disorders, raised a similar point in an email to Canadian Affairs.

She noted that 84 per cent of safer supply participants in the study were already on methadone when they began receiving hydromorphone.

“It would take a lot of fudging to be able to say [safer supply] was responsible for an outcome, when that group was actually receiving two drugs,” she said.

The main study’s authors did not respond to requests for comment. Instead, they directed Canadian Affairs to their May 27 response to Tanguay and Mathew’s critique, also published in The Lancet.

Wraparound care

Critics also say that improved outcomes among safer supply participants may be due to the extensive additional health care they received while on safer supply.

This additional care was evidenced in study participants’ medication costs.

In the year after treatment began, median medication costs for safer supply patients rose by more than $13,000 per person. By comparison, costs for those on methadone rose by about $1,600.

Glen McGee, a statistics professor at the University of Waterloo, says this suggests safer supply participants may have received broader care, including treatment for other conditions like HIV or hepatitis C.

“This could suggest treatment [of the safer supply group] involved more thorough care in addition to [safer supply], which could also account for some of the improved outcomes,” he said.

In their response to Tanguay and Mathew’s critique, the main study’s authors said the additional care is not a flaw — it reflects how Ontario’s safer supply model is designed.

“Embedding hydromorphone prescriptions within other health and social services that address the complex needs of people at high risk of drug-related harms is a deliberate and defining feature,” they wrote.

McGee suggests the challenge of isolating the impact of broader care makes it difficult to draw broad conclusions about safer supply’s role in patients’ health outcomes.

“The analyses in the main paper seem reasonable, but the conclusions are perhaps too strong,” said McGee. “We don’t necessarily know if [safer supply] alone would be as effective.”

Overdose risk

Critics also focused on safer supply participants having a higher risk of overdose than those in opioid agonist therapy.

Although safer supply patients were more likely to stay in treatment than methadone patients, overdose rates remained higher for safer supply patients — even after adjusting for people who dropped out from the methadone group.

The study authors say this is likely because safer supply patients started at higher risk and many continued using street drugs early in treatment.

“The smaller decline among [safer supply] recipients might reflect higher baseline risk and greater ongoing exposure to the unregulated drug supply early in treatment,” they wrote.

They also noted that very few people died in either group, showing that treatment — whether safer supply or methadone — offers protection.

However, Regenstreif urges caution.

“If you peel away the stats language, underneath it all you have a cohort with higher risks of opioid toxicity and other hazards of ongoing drug use,” said Regenstreif.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

I cannot believe the Lancet would allow such a conclusion to be made, given that most of the 'Safer' Supply participants appear to also have been on methadone as well. Depressingly bad science.

I often wonder who these ‘addiction specialists’ are. Clearly they do not have the life experience of someone who has been hopelessly addicted to someone who has changed into a person who can life a meaningful happy life…. The strategies around the safe supply and the coddling of addicts does not work - and we see the evidence blatantly in every city across North America. And round and round we go… looking for solutions when the solutions are: prevention (which is almost nil); compassion for those in addiction; and therapeutic, long term, loving centres who can bring people back to who they are. Until then… round and round we go… the saddest thing is watching the youth die because of ‘safe supply’ - there is nothing SAFE about it!